Assessment

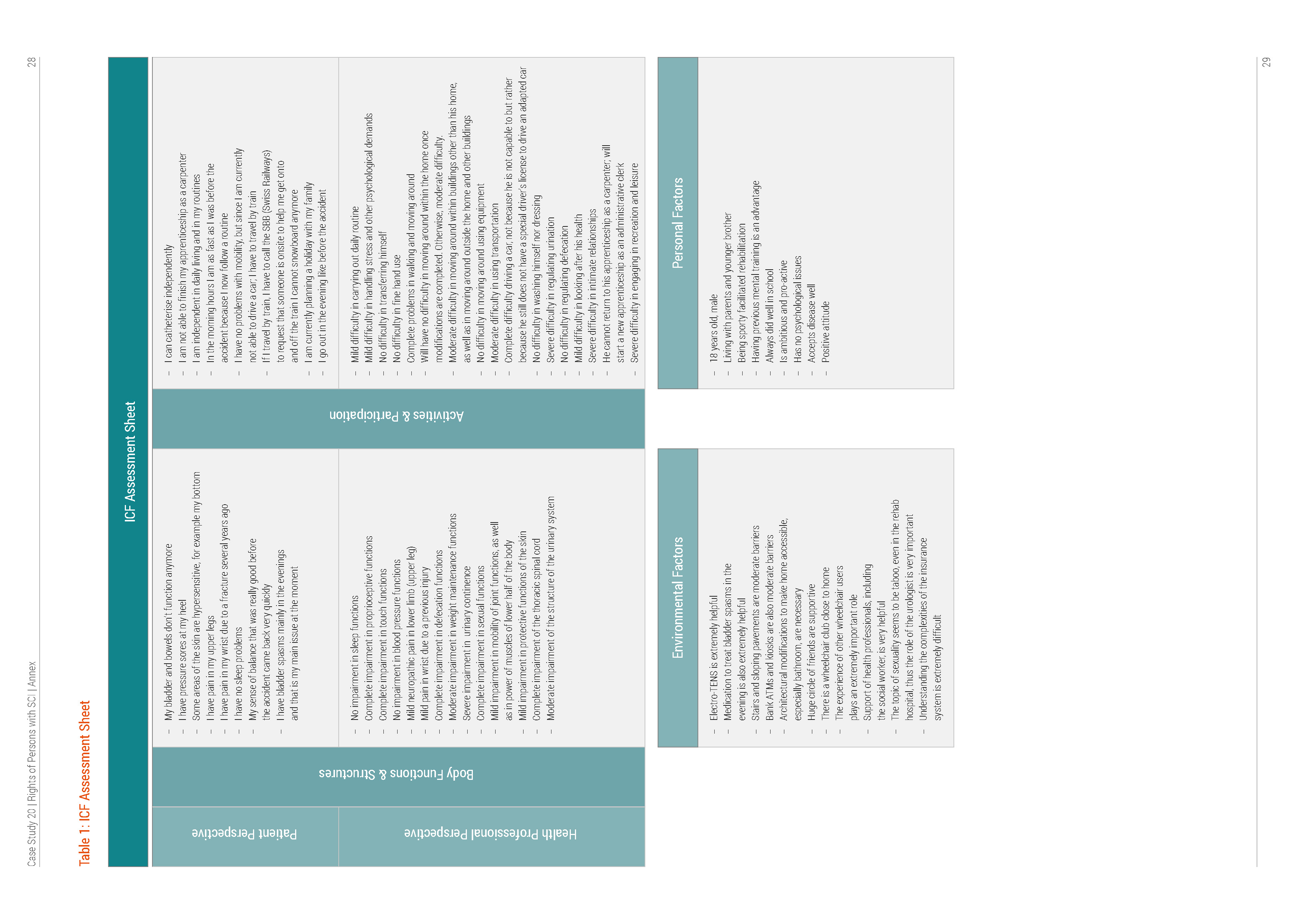

In addition to capturing the health professional’s perspective, as reflected by the battery of tests and evaluations, the comprehensive assessment also captured the patient’s perspective through the interview with Ben. Using the ICF Assessment Sheet, the assessment results were summarised according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) components of body functions, body structures, activities and participation, environmental factors and personal factors.10. The ICF Core Set for spinal cord injury (SCI) in the post-acute context.11 was used as a basis for the documentation of the assessment results.

The comprehensive assessment revealed three major areas in which issues had to be addressed during this Rehab-Cycle® – vocational re-orientation, mobility, and housing.

Vocational Re-orientation

Vocational counselling had already commenced shortly after admission to the rehabilitation centre and before the Rehab-Cycle® began. It was clear from the beginning that Ben had to find an alternative to his pre-injury apprenticeship in carpentry. In the first phase of vocational counselling, his interests and wishes were explored. Thanks to intensive vocational counselling, Ben found a new apprenticeship as an administrative clerk. The apprenticeship was scheduled to start several months after discharge from the rehabilitation centre. In the period of transition before the start of the apprenticeship, Ben had planned to take a language course in the United States as well as participate in a short internship at the same company where he would become an apprentice – in order to gain work experience and get oriented to his new career path.

In planning for discharge and community reintegration, some follow-up questions came up during the comprehensive assessment. These questions had to be answered and issues resolved during the course of the Rehab-Cycle®:

- Who will pay for the language course in the United States?

- Is everything related to the internship with the new employer organised?

- Will Ben receive some income support during the transition period before the start of the new apprenticeship?

Mobility

Besides the questions related to work reintegration, there were also some open questions related to mobility. The comprehensive assessment revealed that Ben had no difficulty in transferring himself, in fine hand use, nor in moving around using equipment. However, he had moderate difficulty in using transportation.

...since I am currently not able to drive a car, I have to travel by train.

Ben at the beginning of the Rehab-Cycle®

After the assessment, the rehabilitation team concluded that being able to drive would be useful for Ben’s work reintegration. This meant that Ben and the rehabilitation team had to explore the possibility of obtaining a special driving license for wheelchair-users and acquiring an adapted car. Again questions came up, this time related to mobility, that had to be resolved during the Rehab-Cycle®:

- What is Ben required to do to take the exam for the driving license?

- What car modifications are needed?

- Has cost coverage for obtaining the driving license and acquiring an adapted car been clarified?

Housing situation

An assessment of Ben’s home conducted before the start of the Rehab-Cycle® resulted in a list of recommended modifications. This was considered in the overall assessment at the beginning of the Rehab-Cycle®. A few questions remained:

- To what extent will the modifications to Ben’s home be realised before discharge?

- Who will pay for all the modifications to his home?

- Is living independently in his own apartment an option?

To help answer these questions relevant laws and regulations and Ben’s rights as a person with disability were considered as part of goal-setting and for intervention planning during this Rehab-Cycle®. The legal framework relevant to Ben’s case is presented in box 2.

Box 2 | Legal Framework in Ben’s Case

Vocational Re-orientationWork participation after SCI is generally considered important for economic self-sufficiency and overall adjustment to disability, and shown to be associated with better outcomes.1213 To enable persons living with SCI to work, employers may need to make necessary and reasonable modifications to the workplace, e.g. wheelchair accessible bathroom facilities, or accommodations to fit the person’s needs, e.g. adjusted work schedule. Providing personal aids (assistive devices) may also be crucial for the person to perform job tasks. If a person cannot return to their previous job, a vocational retraining might be necessary.1213

Article 27, Paragraph 1d of the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)3 calls for legislation to safeguard and promote the right of a person with disability to work by enabling him or her to effectively access, among other things, vocational training. Furthermore, Article 27, Paragraph 1k calls for legislation that promotes return-to-work programmes. In Switzerland, the Federal Law on Disability Insurance (IVG)7 addresses the right to work and outlines work-promoting interventions, which a person with disability is entitled to. The following IVG Articles are relevant to Ben’s case:

- Article 15 - Vocational counselling

- Article 16 - First vocational training

- Article 17 - Vocational re-training

- Article 18 - Job placement and internship, including provisions for a daily allowance during the internship, for when the internship evolves into a permanent job

- Article 21 - Access to assistive devices and technology

- Article 22-25 – Daily allowance provisions and requirements

There are also federal regulations that detail the provisions outlined in laws. For example, the Federal Disability Insurance Regulations (IVV) provides regulations that underpin the IVG and the General Part of the Federal Social Insurance Law (ATSG)4. In Ben’s case, Article 4, sub-paragraph 5.2 of the IVV specifies that he was entitled to an intervention that would enable him to maintain a daily structure and engage in activities until he started vocational re-training. This is referring to Ben’s internship during the period of transition before he started his apprenticeship. Furthermore, under Article 18 of IVV, Ben was entitled to a daily allowance during this transition period.14 Other federal regulations that were relevant for Ben’s case include the Federal Regulations on the Distribution of Assistive Devices through the Disability Insurance (HVI). Specifically, Paragraph 13 in the list of assistive devices enclosed in the HVI specifies Ben’s eligibility for assistive devices and physical adaptations to the workplace as well as environments that prevented him from getting to work.15

Mobility

To facilitate successful work reintegration and to ensure participation of persons with SCI in education and social activities, it is essential that independent mobility, especially accessibility of transportation, is achieved.91213 Moreover, being able to drive has shown to be positively associated with return-to-work after SCI.1316 Inaccessible transportation has been identified as one of the most frequent self-reported barriers for work re-integration, especially in rural areas.91718

Article 9 of the CRPD3as well as Articles 3b, 7, and 15 of the Federal Disability Anti-Discrimination Act (BehiG)5 clearly outline provisions for the accessibility of public transportation systems, including the train and bus stations, airports, the corresponding communication system, the ticket automats, and the transportation vehicles themselves.

Since Ben was leaning more toward the possibility of driving an adapted car, other legislations and regulations applied. For example, Paragraph 10 in the HVI list of assistive devices defines the annual coverage of car adaptation costs. According to Article 8 of HVI, coverage of high-cost assistive devices, such as for an adapted car, would be paid on an amortisation/instalment basis. Article 7 of HIV is also relevant for driving. Article 7, Paragraph 1 stipulates that if special training is a pre-requisite for using the assistive device – in this case the cost of learning to drive an adapted car, the Disability Insurance would cover the training costs.15

Housing Situation

In addition to accessibility at the workplace or of public transportation, a wheelchair-accessible home is crucial for successful community reintegration after discharge from the rehabilitation centre.917192021 According to a study of 123 older persons with SCI published in March 2017, accessible housing was perceived as the most important physical environment factor that supported community participation.21 The most common housing modifications are ramps, wide doors, and adapted bathrooms. Since these modifications can be very expensive, financial resources are required.19

As with vocational re-orientation and mobility, the CRPD, specifically Article 9 Accessibility, also addresses accessible housing issues. In Ben’s case, Swiss legislation that applies to his housing needs include:

- Article 21 of IVG and Article 2 of the HVI, addressing access to assistive devices and technology in general

- Paragraph 14 in the list of assistive devices enclosed in the HVI, detailing the cost coverage for diverse architectural modifications to the home as well as assistive devices, such as a wheelchair lift

- Article 14, Paragraph 1b of IVV, stipulating cost coverage for disability-related modifications of buildings